University-level translation and interpreting (T&I) training has long been a key part of the industry’s goal to ensure the quality of T&I services. Recent technological advancements have highlighted the potential of virtual reality (VR) software in educational settings, and the technology ensures a truly immersive experience, making it particularly relevant for training interpreters. Several institutions have already adopted VR-facilitated interpreter training, such as Monash University, Sabine Braun’s Interpreting in Virtual Reality (IVY) Project at University of Surrey, the EU-funded EVIVA project, etc.

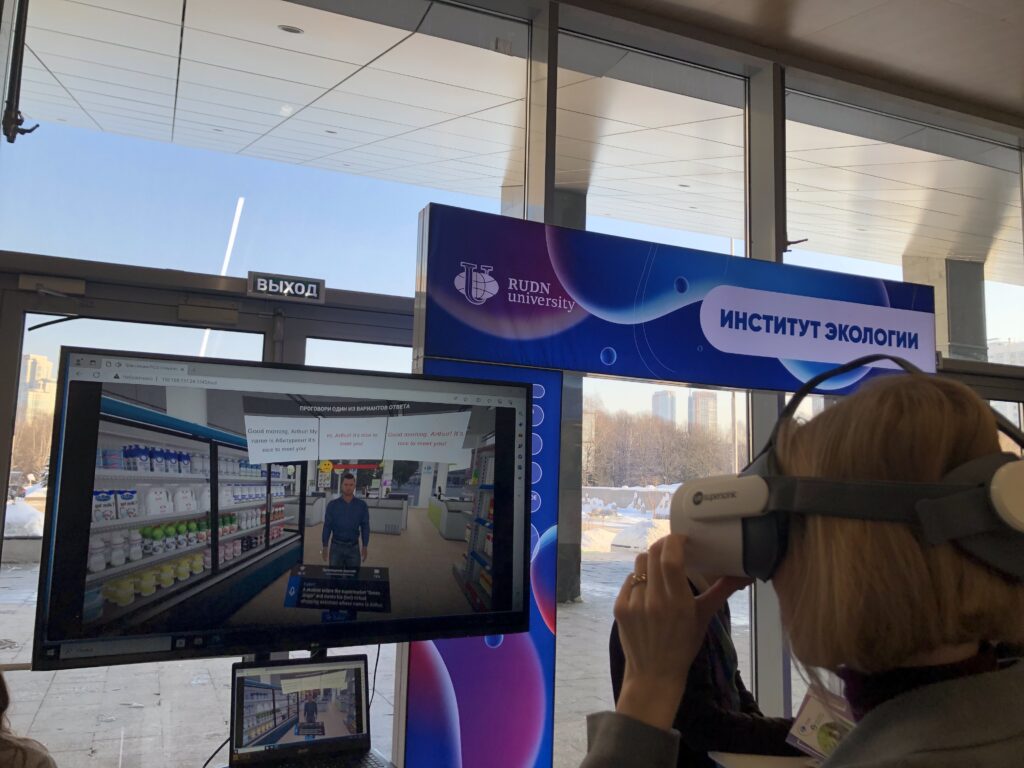

Last year, RUDN University embarked on its own VR journey. The university has offered a four-year professional conversion course in specialised T&I since its foundation in 1960, and over 40% of its full-time undergraduates receive specialised T&I diplomas to complement their regular majors. Using VR-facilitated immersive training to simulate real-world settings is crucial for this programme, as it provides risk-free simulations of highly contextualised situations where standardised speech patterns are required. These include legal and medical settings, technical communications in engineering, science, and ecology, academic communications, diplomatic relations, and others.

For this tool to work in the classroom, it needs to be available in the necessary working language pairs. In Russia, this is generally Russian and other European and Asian languages. The technology also needed to be user-friendly, such that trainers did not need special programming skills. This would allow them to design the content at night and test it in the classroom the next morning, simplifying the path from content design to its use in VR. RUDN University worked with the Russian company VR Supersonic, which has designed a platform and software that met these requirements and currently works with universities that offer specialised world language and T&I training.

VR Supersonic provided a two-month training, during which trainers created scripts (as sequences of domain-specific events) in English, Chinese, and Arabic, with modules on interpreting skills. The courses incorporated situated learning scenarios in such fields as legal, academic, financial, corporate, and engineering. These were then integrated into the VR training pilot, which lasted a term, during which students used all-in-one VR headsets in the classroom for some 20–30 minutes.

This experience has revealed that VR-facilitated instruction enhances interpreters’ code-switching skills, standardised speech patterns used in domain-specific bilingual communications, and awareness of extra-linguistic, context-dependent behaviour conventions. However, in their feedback, students themselves emphasised the importance of human-led instruction, as they work with and for fellow humans, even if they increasingly also use gadgets to help them. RUDN University looks forward to exploring more ways to use this technology in the classroom.

Anastasia Atabekova (RUDN)